In the mountains of Chiapas, Mexico, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation has waged a guerilla war against the Mexican state since 1994. I journeyed to San Cristobal de las Casas in search of the elusive Zapatista movement. Here’s how I visited the Zapatista headquarters in the village of Oventic, and how you can too.

By Richard Collett

‘You are in Zapatista rebel territory. Here the people command and the government obeys.’

Zapatisata warning, seen in Chiapas.

The gates to Oventic in Chiapas were firmly closed. A young teenager, no older than fifteen or sixteen years of age, watched over the roadside from a stone pillbox daubed in revolutionary graffiti. A thick black ski mask obscured his face, but it couldn’t hide his age or the beads of sweat dripping from his brow in the stifling midday heat.

Wearing the tired military fatigues of the Zapatistas, a left-leaning political movement that’s waged a guerilla war against the Mexican government since 1994, the ski-masked guard watched wordlessly as I clambered out of the air-conditioned minibus and into the inescapable glare of the sunshine – accompanied by five or so other tourists who’d made the same journey from San Cristobal de las Casas, the main tourist city in Chiapas.

For almost three decades, the Zapatistas have fought for indigenous rights in Mexico, during which time they’ve carved an autonomous statelet out of the rural highlands and remote jungles in Chiapas, Mexico’s most southwesterly state. They’ve never formally laid down their arms, and the Zapatista movement continues to protest contentious projects to this day, including the ‘Mayan Train’, a controversial new rail route set to link tourist sights in the Yucatan Peninsula.

A second guard appeared by the gates to Oventic, the guerilla headquarters, ‘model village’ and outreach centre of the Zapatista movement. She passed a blank piece of paper and a blunt pencil through the railings, then asked for our names, professions and passports. She disappeared with the hurriedly scribbled list (and our passports), and we waited in the sun for a half hour before she returned with the permission needed to enter Oventic.

Table of Contents

The Zapatista Uprising

“We are sorry for the inconvenience, but this is a revolution.”

Subcomandante Marcos

The Zapatistas erupted onto the international stage on 1st January 1994, when their ragtag army of indigenous farmers, labourers and idealistic students emerged from the jungles of Chiapas to seize control of the city of San Cristobal de las Casas.

“We were celebrating New Year when the guerillas came out at midnight,” I was told by Alex Cesar, a local tour guide who was there in the main plaza of the city when the Zapatistas launched their revolution in 1994. “It was a total surprise. No one knew it was going to happen.”

Named for Emiliano Zapata, a hero of the Mexican Revolution who was assassinated in 1919, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (known in Spanish as the EZLN, or Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) was formed in the 1980s by left-wing revolutionaries recruiting impoverished indigenous fighters to their anti-globalisation cause.

The Zapatista army, comprised primarily of historically oppressed Maya groups such as the Txotil, Tzeltal and Ch’ol, was well-organised, heavily armed with automatic weapons and clad in the distinctive black ski masks that have since become the defining apparel of the Zapatista movement. By morning on New Year’s Day, the guerillas had occupied strategic government buildings in San Cristobal de las Casas, and taken three other cities across Chiapas.

‘The Zapatistas have dedicated their efforts to give themselves a roof, land, work, health, food, education, democracy, freedom, justice, culture and information,’

Paul Romero, La Jornada journalist.

“At first, we didn’t know who they were. We didn’t know what to think,” Cesar recalled. “They took the radio stations and released the prisoners from jails. They didn’t hurt people though, they were considerate, and then a few days later, they left.”

As quickly as it had begun, the Zapatista uprising was seemingly over. The Zapatista army withdrew from San Cristobal de las Casas without a fight a few days later, as brief but bloody engagements between guerillas and Mexican army units in other parts of Chiapas forced them back into the jungles and highlands. A ceasefire was brokered by local priests, and hostilities were suspended on January 12th, 1994.

Except, the Zapatista uprising was far from over. They’d declared war on the Mexican state, and over the next thirty years, the guerillas consolidated their hold in rural areas in Chiapas. Armed violence slowly transitioned to civil resistance, and the Zapatistas used their hard-fought autonomy to build schools, hospitals, and other vital infrastructure developments in impoverished indigenous communities.

Today, the Zapatistas effectively govern their territory outside the jurisdiction of the central Mexican authorities. But while violent conflict may have calmed, as Cesar told me, the Zapatista uprising has never ended:

“The Zapatistas are still in resistance,” he said. “But these days, there is not so much trouble. It’s very passive now. The guerillas said: ‘We will put down our guns, but we won’t hand them over.’ Their guns are sleeping, I like to say.”

Related: The Medicine man of Chiapas

Subcomandante Marcos: The leader of the Zapatista uprising

The Zapatista movement is decentralised, and its structure and the identity of its leaders are shrouded in mystery. During the Zapatista uprising in 1994, though, one man, clad like the rest of the guerillas in a black ski mask and military fatigues, emerged head and shoulders above the other ranks.

Known by his nom de guerre, Subcommandante Marcos became the media figurehead for the Zapatista movement. During the occupation of San Cristobal de las Casas, Marcos addressed the world with a hardened statement that explained the Zapatista uprising in persuasive terms by recalling centuries of indigenous oppression.

“We are a product of 500 years of struggle,” said Marcos. “First against slavery, then during the War of Independence against Spain led by insurgents, then to avoid being absorbed by North American imperialism, then to promulgate our constitution and expel the French empire from our soil, and later the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz denied us the just application of the Reform laws and the people rebelled and leaders like Villa and Zapata emerged, poor men just like us.”

Subcommandante Marcos, educated in philosophy and literature at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, not only had a way with words but a media-savvy, revolutionary image to match Che Guevara.

Typically photographed in a faded military uniform, his face obscured by a black ski mask, Marcos delivered rousing speeches to the media, and he remained the Zapatista figurehead for years to come.

The BBC reported that Marcos had stood down from Zapatista duties in 2014, but Cesar told me that Marcos is still very much still politically active today. “He gives talks and lectures at the university,” said Cesar. “But if you ask the Zapatistas where he is, they will say they don’t know!”

‘But today, we say ENOUGH IS ENOUGH.‘

Subcomandante Marcos

Related: Photos From the Road: The Mayan Ruins of Mexico

What are the Zapatistas fighting for?

‘That vulture came to try and steal your name but now you got a gun. Yeah, this is for the people of the sun!’

Rage Against the Machine, ‘People of the Sun’.

The occupation of San Cristobal de las Casas was a cool and calculated move, and the Zapatista movement was thrown into the international limelight as documentary filmmakers and journalists descended on Chiapas.

With the help of anti-establishment bands like Rage Against Machine, who supported the movement with popular songs like ‘The People of the Sun’, the Zapatista cause made headlines and cemented itself in mainstream popular culture.

Marcos claimed the Zapatistas were fighting the ‘Fourth World War’ after the fall of the communist eastern bloc. Their enemy? Neoliberalism and globalisation, a rising capitalist trend that the Zapatistas believed threatened indigenous claims to land and resources in Mexico.

As Marcos raged in his opening address: “We have been denied the most elemental preparation so they can use us as cannon fodder and pillage the wealth of our country. They don’t care that we have nothing, absolutely nothing, not even a roof over our heads, no land, no work, no health care, no food nor education. Nor are we able to freely and democratically elect our political representatives, nor is there independence from foreigners, nor is there peace nor justice for ourselves and our children. But today, we say ENOUGH IS ENOUGH.”

It was no accident, either, that the rebels had chosen 1st January 1994 to reveal themselves to the world. This was the day that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force, a free trade agreement between the USA, Canada and Mexico that the Zapatistas believed would siphon the indigenous wealth of Chiapas further from its people. As The Atlantic put it: ‘For the Zapatistas, NAFTA represented the recolonisation of their country, and they sought to give voice to their protest through armed struggle.’

“The Zapatistas were fighting for the natives, for their culture and land rights,” explained Cesar. “And because Mexico signed the free trade agreement. This meant that lots of land in southern Mexico was effectively handed over to Canadian mining and US oil companies.”

Related: Izamal: The Yellow City of Yucatan

Visiting Oventic: The Zapatista Headquarters

“Where are you from, and why do you want to visit?” I’d been asked in Spanish by the guard at the gates to Oventic. The black ski masks were intimidating, and I was worried the Zapatistas would be disinterested in allowing a travel writer inside their headquarters.

I said simply: “I’m from England, and I want to write about the Zapatistas.”

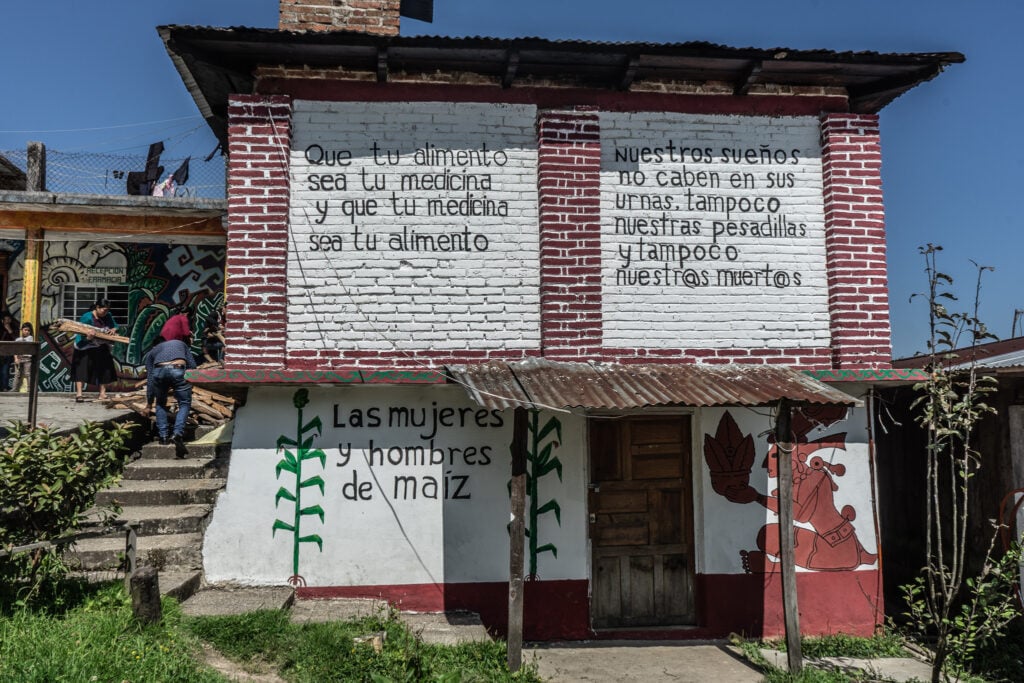

The guards were hardly fussed that I was a writer, and the gates to Oventic were swung open after the interrogations were complete. I took a moment to survey the village ahead of me: inside I could see a single, long street leading downhill, fringed on either side by brightly coloured buildings covered in murals and slogans written in Spanish. At the far end of the village, school children were running around on a playing field, while figures clad in hastily donned black ski masks emerged from doorways and looked towards the new arrivals at the gate.

Oventic is one of 12 ‘Caracoles’, or autonomous communities, located within Zapatista territory in Chiapas. Writing in La Jornada in 2019, Paul Romero explains how these Caracoles (which literally means ‘Snail’ in Spanish) were first established in the wake of the Zapatista uprising in 1994, when the movement took control of as many as 38 municipalities across Chiapas.

Romero also explains how each Caracole is run by an autonomous ‘Good Government Board’, through which ‘That emancipating form of power is woven in which rulers become servants, people who will rule by obeying the people’.

The leaders who sit on these ‘Good Government Boards’ are only ever transitory, and regular rotation ensures that power is shared and constantly moved within the community. These local governments run their Caracoles independently, and as Romero says, they strive to improve the lives of those who live within: ‘Anyone who visits Zapatista territory can perceive the achievements of this exercise of self-government. The Zapatistas have dedicated their efforts to give themselves a roof, land, work, health, food, education, democracy, freedom, justice, culture and information.’

Read more: 21 Best Things to Do in San Cristobal de las Casas

Oventic: The Zapatista Outreach Centre

“No questions”, I was told with authority as the gates to Oventic closed.

The Zapatista movement is notoriously insular, and in theory, the Caracoles are entirely self-sufficient, accepting neither outside help nor donations from governments, NGOs or charities.

Despite their insular nature, Romero explains in his article that actually, the original Caracoles were always intended to be ‘meeting points between the cultures of the Zapatista peoples and the other cultures of Mexico and the world.’

In this respect, Oventic functions as a sort of outreach centre, and while tourists aren’t exactly encouraged to visit, they aren’t necessarily turned away. The Zapatistas even put on tour guides (clad in ski masks, of course) to show us around.

The houses had concrete bases, tin roofs and wooden sides, but they were all brightly painted with artistic murals. The artwork depicted revolutionaries, snails caracoles) dressed in black ski masks, and Maya symbols of corn and life. There were lessons taking place in the primary school, and people were carrying out mundane tasks like hanging laundry out to dry (including black ski masks) and washing cars.

We were led into a small museum, cafe, and gift shop, where tacos and ski masks were being sold to fund the revolution. Photographs of Marcos and other guerillas were displayed on the walls, as were pictures of a Zapatista army unit playing a football match in their trademark ski masks.

As we walked around Oventic, the guards loosened up and laughed, although none removed their ski masks in our presence. They were happy enough for me to take photos of the elaborate, colourful Zapatista murals and revolutionary slogans painted on the buildings, so I thought I’d try my luck at asking a few questions about the village in basic Spanish. “Is Marcos here?” I asked. “No questions,” I was rebuked. “How many people live in Oventic?” I tried again. “No questions,” came the reply.

Related: The Mayan Ruins of Ek Balam

Was the Zapatistas movement successful?

Given the Zapatistas have always been notoriously secretive and selective in their communications with the outside world, the lack of answers from the guards came as no surprise.

There’s a deep-seated mistrust of outsiders, something that stems not just from centuries of exploitation at the hands of colonisers, but from recent action (and inaction) by the Mexican government since the Zapatista uprising.

In 1996, for example, the Zapatistas and the Mexican government then in power agreed on the San Andres Accords, a series of principles supposed to guarantee autonomy, respect and representation for indigenous groups in Chiapas. Subsequent Mexican governments failed to enact the accords, leaving the Zapatistas in a perpetual state of conflict ever since.

This enduring state of mistrust was most recently apparent during Covid-19, when it was reported by the BBC in 2021 that Zapatista territories in Chiapas were refusing vaccinations issued by the government.

But have the Zapatistas been successful in their aims? Writing in 2018, the Guardian reported that the Zapatistas numbered some 300,000 citizens across its autonomous zones. Originally, Zapatistas controlled just five Caracoles, but in 2019, an official communique announced that this number had expanded to 12. In this respect, the Zapatistas have proven successful in growing their territory in Chiapas, while the Guardian article also reported that each Caracole had doctors, healthcare, and schooling.

Women also play a more equal role in Zapatista society, and almost half the fighters in the original EZLN guerilla army were female. In 2018, National Geographic even reported that the Zapatistas held the ‘First International Gathering of Women Who Struggle’ summit. Men were not allowed to take part, but they could: ‘assist with cooking, cleaning, and childcare duties so that women could freely participate.’

Read more: 18 Things to Do in Chiapas

The Zapatistas today

The Zapatista’s military arm has calmed down in recent years, and their priorities have become less global in scope, and more focused on consolidating their autonomy in Chiapas. The Mexican government has never recognised this autonomy, nor do they actively fight the Zapatistas.

Cesar summed up the situation of the Zapatistas today quite succinctly, when he told me: “The Mexican government doesn’t want to arrest them anymore, it was over 25 years ago now. They have been invited to form a political party to take part in elections but that’s not what they want to do. They just want their autonomy and to run their own affairs.”

The Zapatistas also continue to fight for indigenous rights across Mexico, with their latest protests railing against the building of the controversial Mayan Train.

“The Zapatistas are against the Mayan Train, which is supposed to connect Chiapas with the rest of the country for tourists,” explained Carlos, another tour guide who showed me around San Cristobal de las Casas later in my trip. “But it’s not needed. It would be a quick tour; one that doesn’t show you anything. There’s no enrichment, you would just go from one stop to the next, taking pictures.”

Carlos, who works in the walking tour business, slated the Mayan Train for its superficiality, but indigenous rights groups and environmentalists across southern Mexico are more concerned by the potential destruction the new train route could cause.

This over budget rail project is set to link tourist sights such as the Palenque Ruins in Chiapas, with tourist centres such as Cancun and Playa del Carmen on the Yucatan Peninsula. There are claims, however, that the indigenous groups have been forcefully relocated, that rare jungle habitats are being destroyed, and that ancient Mayan sites are being ruined.

For these reasons and more, the Zapatistas have been heavily critical of the project, with the Yucatan Times running a recent headline that read: ‘Mayan Train ignites anger amongst Zapatistas.’

Read more: How Many States in Mexico? Everything You Need to Know.

Zapatourismo in San Cristobal de las Casas

Although they left San Cristobal de las Casas days after occupying it in 1994, the Zapatistas left an enduring mark on the city. Like many who live here, Carlos is a fervent supporter of the Zapatistas – at least in spirit. “The Zapatistas fight for justice and equality,” he told me on his walking tour. “And they fight for a planet that’s based on the dignified existence of the indigenous groups, not the existence of governments.”

This revolutionary spirit is apparent across the city, which is less than an hour’s drive from the Zapatista village of Oventic. The media appeal of Marcos and the Zapatistas brought a wave of tourism to the city, an unusual travel trend dubbed ‘Zapaturismo’.

Zapaturismo has taken on a new age element (“It became a hippie town”, said Carlos), and of the many tourists walking San Cristobal de las Casas’ pedestrianized Turismo streets, very few venture to meet the Zapatistas in Oventic. The city itself is home to Zapatista-themed art galleries and souvenir shops, where you can learn more about the movement and support the Zapatistas through your purchases. There are Zapatista themed wine bars and upscale cafes, which for many, is enough to satisfy their revolutionary cravings.

“If you see a red star outside a shop it means you will be supporting the Zapatistas and will be supporting the movement,” explained Carlos. “The Zapatistas are big producers and they send their products out to towns and cities across Chiapas.”

Indeed, many of the same souvenirs I saw in San Cristobal de las Casas I’d seen being manufactured and sold in Oventik. Another big export is Zapatista Coffee, which is sold in cafes across the world to raise funds and awareness for the movement. Of course, this begs the question, are the Zapatistas truly self-sufficient if they’re being funded by tourism?

Zapaturismo, inspired by an anti-globalist agenda, has also had the somewhat ironic effect of turning San Cristobal de las Casas into a global city. “After 1994,” said Carlos. “The city grew massively. There was a huge level of globalisation. These days, there’s even a German guy selling Thai food in the Mexican plaza!”

Read more: Is Mexico a Country? Everything You Need to Know.

How to visit the Zapatistas

The restaurants, cafes and wine bars of San Cristobal de las Casas are a far cry from the autonomous Zapatista territories in the surrounding highlands. The Caracoles are no Utopia, but rustic places where the communities eke out a hard living from a tough land with little outside assistance.

If you want to learn more, then it’s possible to visit the Zapatistas themselves on a day trip from the city. They won’t answer many questions, but you can see what they’ve built, how they live and try to fathom what they stand for in Oventic.

Oventic is located around an hour’s drive from San Cristobal de las Casas. It was surprisingly easy to visit using public transport. First, I walked to Mercado Viejo, a marketplace located ten minutes’ walk north of the main square in the city. Keep the big marketplace on your right-hand side, and continue walking north for around 300 more metres. You’ll see taxis and minibuses waiting around on the side of the road.

Walking route from Plaza 31 de Marzo to rough location of Oventic transport.

Ask for Oventic, and you’ll be pointed in the right direction. Once you’ve found a vehicle heading to Oventic – this could be a shared taxi (Combi) or shared minibus (Colectivo) – you’ll need to wait for it to fill up before it departs. I paid 57 Mexico Pesos each way, and the van filled up quickly when a group of Italian tourists arrived. You might not be so lucky, and may have to wait. If you’re not concerned with the budget, then you can easily hire a taxi to take you the whole way and back again; probably for less than USD 20.

It’s a winding, mountainous road north to Ovetic, but within an hour you should be dropped outside the gates of the Zapatista headquarters.

Before I’d left, Carlos had told me rather dramatically: “This is a low-intensity war, this is a resistance. If you visit, be mindful of why you are going there, take your passport and have your intentions ready. But be prepared to be turned away.”

No one in the group had given the Zapatistas prior warning of our arrival, but no one at the gates was phased. They asked to see our passports and asked what our jobs were, and as Carlos had suggested, I was honest about my intentions to write about the trip. We were all allocated ski mask wearing guides, then shown around Oventic. At the end, I had lunch in the cafe before catching a collectivo back to San Cristobal de las Casas. Simple.

Be warned though, it’s best to arrive early. Another group arrived as we were leaving, and they were turned away because it was after 12pm. There’s no guarantee you’ll get in at any time, either, so as Carlos also suggested: be prepared to be turned away.

Driving route from San Cristobal de las Casas to Oventic, Chiapas.

There are no formal tours to Oventic, but there are informal fixers and guides who might be able to help. Carlos suggested visiting TierrAdentro Restaurante, a Zapatista supporting business in supposed contact with Oventic (they sell ‘revolutionary omelets’). They might be able to confirm if the Zapatistas are currently hosting visitors or not.

You can also contact Cesar, quoted in this article, who runs the tour company Alex y Raul Tours. They primarily organises tours to Chamula, an indigenous village near San Cristobal de las Casas that’s known for its unusual blend of Catholicism and Mayan religious practices (chickens are regularly beheaded in the church). But he also said that, given a few days’ notice, he can use his Zapatista contacts to organise a visit to Oventic.

Since I travelled here pre-covid, it also seems there are a number of new initiatives and tours which might allow you to spend more time with the Zapatistas. Schools for Chiapas organise volunteer placements with the Zapatistas, there now appears to be an Oventic Language School and there’s an Airbnb tour guide offering Zapatista experiences.

‘Para todos todo, para nosotros nada.’ (For everyone, everything. For us, nothing).

Zapatista slogon.

Related: Things to Do in Merida Mexico – And a Few Things to Eat Too!

Zapatistas: FAQs

Viva la Revolucion, and safe travels if you’re visiting the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico! The following FAQs may answer any important questions you have about visiting the Zapatistas in Oventic.

Where is Oventic, Chiapas?

Oventic is a Zapatista Caracol, outreach centre and supposed headquarters of the Zapatistas in Chiapas. The village is located one hour north of San Cristobal de las Casas. It’s possible to travel to Oventic by taxi, collectivo or combi.

Do I need a passport to visit the Zapatistas?

Yes, you do need a passport to visit the Zapatistas. They function independently of the Mexican government, and may request to see your passport before allowing you into Oventic.

Could the Zapatistas turn me away from Oventic?

Yes, there’s no guarantee that the Zapatistas will allow you into Oventic. You can try to check in advance by speaking with tour guides in San Cristobal de las Casas, but ultimately, it’s always at the discretion of the guards.

Can I take photographs when I visit the Zapatistas?

You can take photographs of the buildings and murals during your tour of Oventic. It’s forbidden to take photographs of the Zapatistas, even when they are wearing their ski masks.

Can I stay the night at Oventic?

There are dormitories at Oventic, although you may need to be on an organised and official programme (such as a language learning programme, for example) to spend the night here.

Is it safe to visit the Zapatistas?

The ski masks are certainly intimidating, and the entry process is a little daunting, but I never felt unsafe when I visited the Zapatistas. As always, though, remember that this is rebel-held territory outside of central government control. Anything can happen, including armed conflict.

Related: How to Travel to the Breakaway Republic of Abkhazia!

What languages do the Zapatistas speak?

The Zapatistas speak a mixture of Mayan languages, such as Tzotzil and Chol. They also speak Spanish, so bring a phrasebook or brush up on your Spanish skills in San Cristobal de las Casas.

From adventures in breakaway territories to interviews with former guerrilla fighters, Travel Tramp’s ‘Travel Stories’ go deeper than most. Follow the action on the blog, or like us on Instagram and Facebook for the latest updates

Recent Comments